31 July 2025

Insights into the ego-culture and symbolism of graffiti writing and street art

With the global embrace and professionalization of street art and graffiti, and their acceptance into museums, interest in their origins has surged. Questions arise; where does it come from, what are the rules, what distinguishes street art from graffiti, should graffiti belong in museums, how do you preserve the culture, is it empty symbolism or deeply meaningful, and what happened to the rebellion at its core?

First, let’s dismiss the notion that street art and graffiti are the same, they are not. Graffiti is widely recognized as the foundation from which street art emerged. And yes, in some parts they are equal: public space is their canvas, spray cans are the tools, and both are visually striking. However, their essence diverges significantly.

In the 1970s the New York City teenagers start to make their graffiti mark on the 600 miles of MTA steel and machinery that ran like blood vessels through the city. They are going “All city” which means that a graffiti writer has made his mark in all five boroughs, from Staten Island to the Bronx, sending his or her creation rolling over the tracks to be seen by people in all parts of New York City. This was the ultimate ego trip: seeing your name on hundreds of subway cars became a form of ‘personal branding’ and advertising in its rawest form. No one understood the unspoken power of repetition better than a graffiti writer. Not hindered by regulations, their motto was simple: “bigger, better, more” or as in graffiti terms, “getting up.”

“It’s a matter of getting a tag on each line and each division. You know, it’s called, going all-city. People see your tags in Queens, Uptown, Downtown- all over.” Skeme in the movie Style Wars, 1983

The essence of graffiti

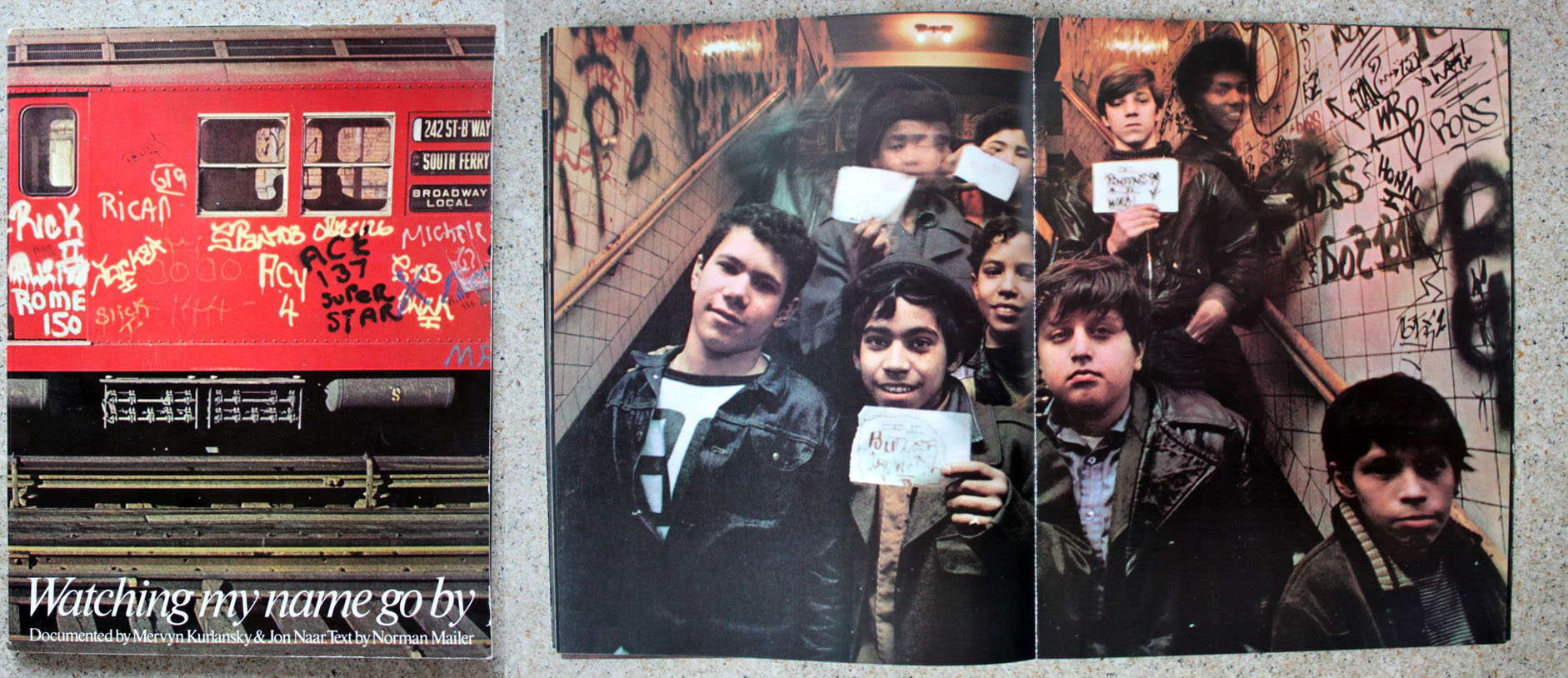

Graffiti, was driven by rebellion and based on a sense of community formation. It was for the writers themselves, ‘normal people’ were excluded. Writers tagged repeatedly, creating pieces that gave form to their alter egos. The creativity lay in their lettering style, evolving from simple single-line tags to complex creatons that became unreadable for outsiders. It is a name-driven culture. For those looking for more depth, the early years of this culture are beautifully captured in 1974 by graphic designer Mervyn Kurlansky, (partner in the design consultancy, Pentagram), in the book with the title that say’s it all: “Watching My Name Go By”.

Art in the streets

Street art compared to graffiti is different, often uses letters but not as a focus point. It prioritizes accessible imagery and thought-provoking messages aimed at a general audience. Using figurative visuals or critical enhancements to existing structures or ads, it bridges artistry and commentary. Keith Haring was at the forefront of this transformation, merging the divide between high art and graffiti culture, shaping the emergence and evolution of street art during that era. He created a visual language that was accessible, communicating its meaning to a diverse audience, irrespective of their cultural, social or educational backgrounds.

Street art often carries social critique. Banksy being the most famous example of JR, originally a graffiti writer, also uses large-scale installations to encourage public dialogue. However, nowedays murals sanctioned by building owners or housing corporations can feel a bit fake. Sometimes these murals are finished with a coating that makes illegally applied graffiti easy to remove. A greater contradiction is hard to imagine. What’s sometimes missing is the raw surprise and impact that the street art offered further back in time, for example in the Amsterdam punk graffiti era. Bold statements using block brushes or stencil critiques with socially critical texts or images of abuses in society. Today, a big part of the street art focuses on scale, technique, and aesthetics rather than potent messaging.

The transformation of the culture

But also, over the last 15 years, both movements have radically evolved and blended. Collaborations and exhibitions are being organized worldwide. This also leads to wonderful crossovers. For example, very recently, the Brazilian artist duo OSGEMEOS is cooperating with Märklin. Yes exactly, Europe’s leading producer of high-quality model railways. They are presenting two new, strictly limited art wagons in the serie ‘Märklin Message Wagons’. The Brazilian artist duo has been world-famous for decades for their colorful, vibrant works of art in the streets and major graffiti culture based exhibitions. Their colorful, cheerful figures are emblazoned on buildings, public places, and airplanes. They are particularly fascinated by trains. The Märklin brand is making a name for itself in the graffiti and street art world as a supporter of contemporary art, including limited edition scale models. The circle is beautifully complete in this one.

Preserving the culture graffiti heritage

Another important aspect in a culture that become so big and important is the heritage of it. Graffiti heritage and its preservation has taken on serious proportions. Robin Vermeulen, as part of his graduation research at the Reinwardt Academy – Bachelor’s in Cultural Heritage – published a study in 2015 in which he explored what opportunities exist for the preservation of graffiti within a heritage context. The conclusion: graffiti is best preserved outside of formal heritage frameworks, by the graffiti scene itself. This is often referred to as DIY (Do It Yourself) heritage management. Graffiti is, by definition, ephemeral, not only in its physical form but also in its documented form. The ultimate way to preserve graffiti is by documenting the material manifestations of the phenomenon. This applies both from the perspective of heritage institutions and from that of graffiti writers and enthusiasts.

The Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands (Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed) has emphasized in the ‘Faro Convention’ that everyone has the right to attribute their own meaning to heritage. The underlying stories have cultural-historical value and contribute to both the tangible and intangible legacy of Dutch society. In the Netherlands this is the field and domain of the Dutch Graffiti Library

I am Marcel van Tiggelen, alongside my role as Project Director at TD Cascade, together with my brother Richard, the founder of the Dutch Graffiti Library. We are dedicated to preserving the counterculture of graffiti by collecting, archiving, publishing, and maintaining documentation for over 35 years. At the Dutch Graffiti Library we preserve graffiti through documentation, with a strong focus on capturing the origin stories, narratives, and customs within the culture. As a culture that is embraced worldwide as the foundation of modern art movements and widely used in fashion and design it is therefore of historical importance that this heritage of the street is presented, displayed, and inspires in a meaningful way for the generation growing up today. This is something I have been passionate about all my life!